Isles of Shoals

In 1614, when the venerable Captain John Smith dropped anchor among the Isles of Shoals, he was so captivated by them that he named them “Smith’s Isles” for himself. “Of all foure parts of the world that I have seene not inhabited,” he wrote, “could I have but the meanes to transport a Colonie, I would rather live here than any where.”

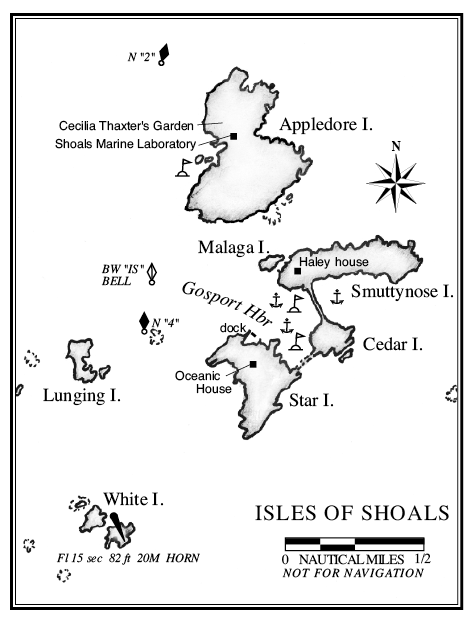

Lying just six miles southeast of the entrance to Portsmouth Harbor, five of the nine islands are in Maine (Duck, Appledore, Smuttynose, Malaga, and Cedar) and four are in New Hampshire (Star, Lunging, White, and Seaveys). The islands are spectacularly scenic, and their long history is crammed with tales of buried treasure and bloody Indian attacks.

Smith’s name didn’t stick. More impressive than his praise or his unmatched contributions to the exploration of New England were the schools, or shoals, of cod near the islands, in an abundance never before seen by European fishermen. By the eighteenth century, the Isles of Shoals were considered one of England’s most valuable colonies because of the astounding quantities of cod caught, dried, and shipped home.

The early cod-fishing communities were based primarily on Smuttynose and Appledore Island, but when the Massachusetts Bay Colony started to levy onerous taxes on the islanders in 1680, they crossed over to New Hampshire’s Star Island, named their new town Gosport, and continued their thriving fishing industry for another century. During the Revolution, however, everyone was evacuated to the mainland. Those who returned to Star Island after the Revolution acquired a reputation for “laziness, drunkenness, lawlessness, and cohabitation,” and the community never returned to its former prominence.

The islands had a modest revival in the nineteenth century, and a widely read poet, Celia Thaxter, grew up in the midst of it. Thaxter was the daughter of Thomas Laighton, the lighthouse keeper on White Island. Aware and sensitive at an early age, she referred to the area as “these precious isles set in a silver sea.”

Enterprising Laighton built Appledore House around 1850 and publicized it as the first resort hotel between Nantucket and Eastport, Maine. At the peak of their combined popularity in the 1890s, both Appledore House and Celia Thaxter attracted such literary and artistic figures as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Sarah Orne Jewett, Childe Hassam, and John Greenleaf Whittier.

The rival Oceanic House, built on Star Island in 1872, advertised itself as “an ideal summer resort of the highest class and full of historic associations. Preeminently the place for the tired worker. No noise, no dust, no trolleys.”

With the advent of the automobile, the Isles of Shoals resort business declined, and in 1915 Star Island was sold to an association of Unitarians and Congregationalists for $16,000 as a conference center for religion, natural history, and the arts.

Approaches

The approach to the Isles of Shoals is easy. Coming from the south, aim for the 82-foot light on White Island, leaving it to port. Pass between nun “4” on Halfway Rocks and Lunging Island to find red-and-white bell “IS” (42° 58.87’N070° 37.26’W) at the mouth of Gosport Harbor.

Coming from the north on a clear day, you may be able to see the Appledore tower and the cupola on the former lifesaving station from as far away as Boon Island. Stay well clear of low and featureless Duck Island, which tends to merge with Appledore. In particular, beware of long Southwest Ledge if you are running a course from the red groaner “24YL” to nun “2” off the northwest tip of Appledore. From nun “2” head for red-and-white bell “IS” at the harbor mouth.

From the east, you can enter Gosport Harbor through the “back door” between Appledore and Smuttynose. Favor Smuttynose to avoid the ledge making out southward from Appledore. Round Malaga Island into the harbor.

Anchorages, Moorings

The only harbor in the Isles of Shoals is Gosport Harbor, between Star, Cedar, and Smuttynose Island, so it is likely to be crowded. On warm weekends you will be competing with day-trippers from Portsmouth and Kittery as well as cruising boats, sometimes rafted four and five abreast. Even on weekdays there may be 10 or 20 boats here, so arrive early to choose a spot.

Holding ground is very poor, in kelp and rock beds. In most harbors you can trust your anchor more than unknown moorings, but in Gosport Harbor it is better to pick up a mooring. MThere are a number of large, private moorings scattered around the harbor. Six of them are marked “PYC” and maintained by the Portsmouth Yacht Club for use by its members. The club generously welcomes visiting yachtsmen to use the moorings if they are unoccupied but asks that you vacate your mooring if a member needs it.

If you are forced to anchor, try to set your hook in the mud up in the cove between Star and Cedar Island without fouling lobster buoys and moorings while leaving enough swinging room should the wind swing around to the west. Failing that, find a 21-foot spot farther out, avoiding the 48-foot areas. Use a good heavy anchor with a tripline.

Gosport Harbor is totally exposed to a good northwest blow, in which case, get out of the harbor and head for Portsmouth or go to sea. With enough visibility, you can power around Smuttynose and reset the hook on the eastern side of the breakwater between Cedar and Smuttynose. Depth varies from 8 to 18 feet. The bottom has good holding in sand and boulders, but expect a swell.

Star Island

The Oceanic House is no longer a hotel, but the Star Island Corporation (603-430-6272; starisland.org) generously allows yachtsmen to visit the island from 10am to dusk on weekdays and from10am to 3:30pm on Saturdays and Sundays. One of the young dockhands, known as “Pelicans,” can pick you up in their tender or you can dinghy to the float, which has room for eight dinghies.

Please be respectful of any conferences in progress. The Oceanic House has Fa snack bar, a gift shop, and restrooms. The Vaughn Cottage, open daily from 1pm to 3pm, displays Celia Thaxter memorabilia. There is a small playground for children.

Near the eastern end of the island is Betty Moody’s Cave, described in Robert Carter’s 1858 Summer Cruise on the Coast of New England. “Early in the old Colony times,” Carter relates, “the Indians from the mainland made a descent upon the islands, and killed or carried off all the inhabitants except a Mrs. Moody, who hid herself under the rocks with her two small children.” As the Indians combed the island, “the unhappy mother, unable to keep her infants quiet, killed them with a knife to prevent them from crying.”

From there, walk south along the coast to find Miss Underhill’s Chair, a rocky perch from which a romantic young island schoolteacher was swept away by a great wave.

Smuttynose and Malaga Island

Smuttynose and Malaga Island. Named for the dark rocks at its eastern end, uninhabited Smuttynose boasts enough history for several volumes. In a little graveyard behind his 1750 cottage lies Captain Samuel Haley, who lived to be 84 and was, according to his headstone, “a man of great ingenuity and industry.” On this little island Captain Haley built a 270-foot ropewalk, a saltworks for curing fish, windmills to grind wheat and corn, blacksmith and cooper shops, a bakery, a brewery, and a distillery.

Pirates such as Captain Kidd and Quelch are reputed to have visited Smuttynose. In 1720 Edward Teach, known as Blackbeard, arrived on Smuttynose with his new young bride, who happened to be his fifteenth. The arrival of the British fleet, though, brought a quick end to the honeymoon. Being short on sentiment and long on self-preservation, Blackbeard fled, leaving his wife behind to wait for him in vain until her death fifteen years later. The ghost of Blackbeard’s wife, they say, still roams the shores crying, “He will come back. He will come back.”

For once, stories of buried pirate treasure have proved true. Captain Haley found four bars of silver under a flat stone and used the proceeds to build a breakwater connecting Smuttynose to little Malaga Island, creating Haley’s Cove.

Smuttynose was also the site of a grisly double murder on the cold night of March 6, 1873. Six Norwegian immigrants—three couples—lived in what would become known as the “Hontvet House,” which was owned and operated as a boarding house by the family of Celia Thaxter on Appledore Island. The men had sailed to the mainland on a bait-buying trip but had not returned by nightfall. The women turned in. Suddenly, in the depth of the night, they were awoken by a brutal attacker swinging an ax. Two of the women were killed. The third, Maren, escaped and hid among the rocks with her dog Ringe.

Maren survived the night in nothing but her bloody nightdress. She later identified the murderer as Lewis Wagner, a Prussian fisherman who had helped the Norwegians bait trawls the previous summer. Lewis supposedly rowed the 12 miles to Smuttynose to rob the Norwegians of money he knew they were saving for a new boat. He was hastily tried and convicted and hanged despite his proclamations of innocence. The story has been intriguing the American imagination ever since, most recently in Anita Shreve’s book The Weight of Water, and the ghoulish can find the supposed murder weapon on display in the Portsmouth Athenaeum.

Row ashore—if you dare—at Haley’s Cove and land at the little beach behind the breakwater. This is a lovely spot for a picnic, peaceful and secluded, and you can swim in clear water off the beach. Nearby are two houses. The Haley cottage has been restored, and little Roz’s cottage is used as a base for camping groups.

Smuttynose is still privately owned by descendants of Celia Thaxter, but they have protected with a conservation easement to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and they generously welcome respectful visitors. It is managed by volunteer rangers and shared with 3,000 pairs of gulls who nest here. A guest log is outside Roz’s cottage.

Appledore Island

An ample freshwater spring enabled Appledore to be one of the most populated English settlements in the 1660s. But when the island became a township in 1680 and Massachusetts assessed taxes, its 40 families deconstructed their houses and rebuilt them on Star Island, just across the New Hampshire line. Most of the island is now owned by the Star Island Corporation, and the public is welcomed during daylight hours.

Current inhabitants are mostly seagulls and summer students from Cornell University and the University of New Hampshire who work at the Shoals Marine Laboratory field station. The island is also a migratory way station for more than 125 species of birds, and harbor seals, whales, porpoises, and dolphins frequent its waters.

Shoals Marine Lab (shoalsmarinelaboratory.org) maintains several Mmoorings on the west side of the island. Visitors are welcome to use them for limited periods, but this is not a good place to spend the night. Row ashore to the dock, sign in, and pick up a map of the island. To the left of the dock there is a delightful, well-protected tidal pool for swimming.

To the north, beyond the lab building, is the Laighton family cemetery, the foundation of the old Appledore House, and a re-creation of Celia Thaxter’s garden, as described in her book An Island Garden, illustrated by Childe Hassam. Lichen-covered whale bones lie near the Lab’s dinner bell, up near Kiggins Commons. Stay on the trails to avoid nesting gulls and rampant poison ivy.